What happens when brands turn off the tap?

You’re a CEO in the middle of a pandemic-level crisis. Shareholders are nervous, and you and your brand are facing all kinds of uncertainty. Do you …

Cut your marketing budget

Maintain your spend

Double down?

During the pandemic, Coca-Cola was looking to save money, so they cut advertising by 35% and their entire comms budget by $2 billion.

We can’t imagine having a comms budget so massive you could cut $2 billion from it and still have a comms budget, but here we are.

Coca-Cola CEO James Quincey said, “We thought no amount of marketing is going to make much of a difference, so we pulled back heavily.”

Did it work?

Not quite. Coca-Cola lost 11.4% in net revenue. To save $2 billion, they lost $4 billion.

Pepsi maintained their ad spend and grew revenue by 5%.

Procter & Gamble decided to double down.

CEO Jon Moeller said, “The best response … is to push forward, not to pull back.”

Moeller had been P&G’s CFO, so this was a former CFO advocating for more marketing.

He went on to say, “There’s a big upside here in terms of reminding consumers of the benefits they’ve experienced with our brands … which is why it’s not time to go off-air.”

Exactly. The reason you do marketing in the first place is to build and reinforce mental availability so that people remember who you are, how you solve their problems and how you make them feel.

Pepsi and P&G won because they were committed to playing the long game.

Of course, Coke isn’t going anywhere. But for every $1 they “saved” from that short-term cut, it cost them around $1.85 to regain lost market share.

But what happens when a brand cuts its marketing budget to almost nothing?

Direct Line Group is one of the largest insurance companies in the UK, home to leading insurance brands including Churchill and Privilege.

Churchill has a healthy marketing budget. Privilege used to.

Back in 2006 or so, price comparison websites started appearing in the UK, which upended the insurance market. People could directly compare prices and coverage, and insurance brands with larger overhead seemed to be at a disadvantage.

To compete, Direct Line Group repositioned Privilege as a no-frills, low-cost insurance brand. That meant as little overhead as possible and almost no marketing.

Potential customers would pretty much only see Privilege when it popped up in a price comparison search.

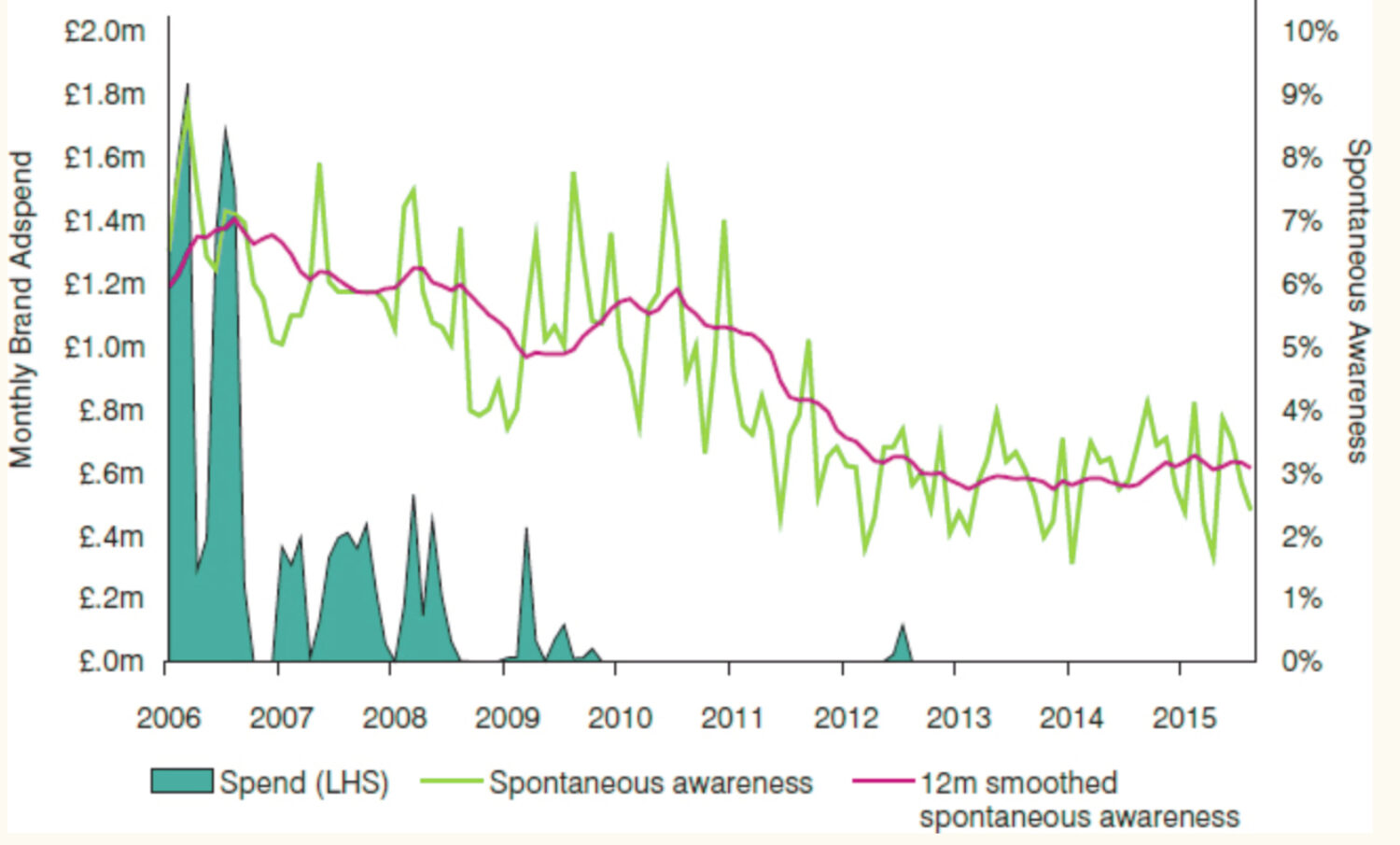

Here’s what happened:

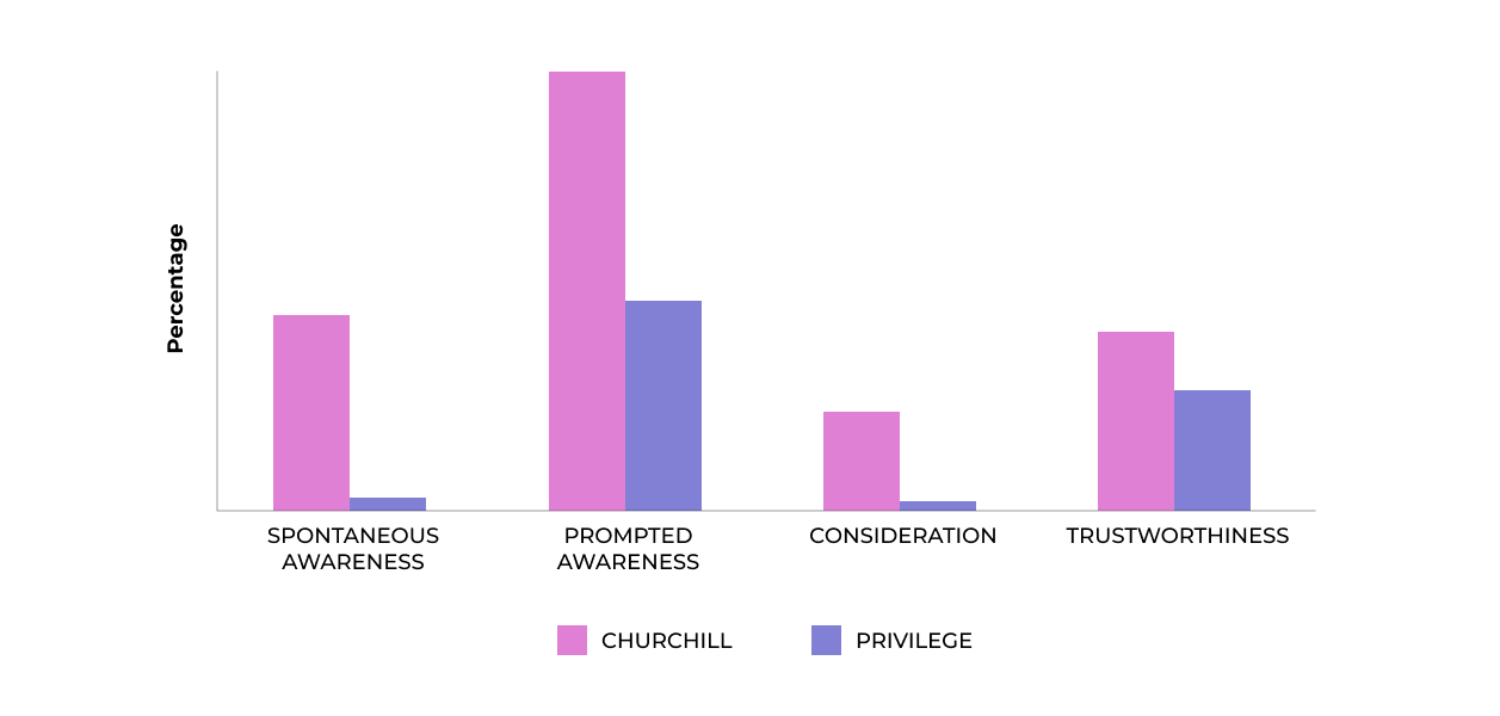

Source: WARC “Direct Line Group: They went short, we went long”

It took a while, but with no ads to reinforce mental availability, spontaneous awareness (recall) of Privilege declined significantly.

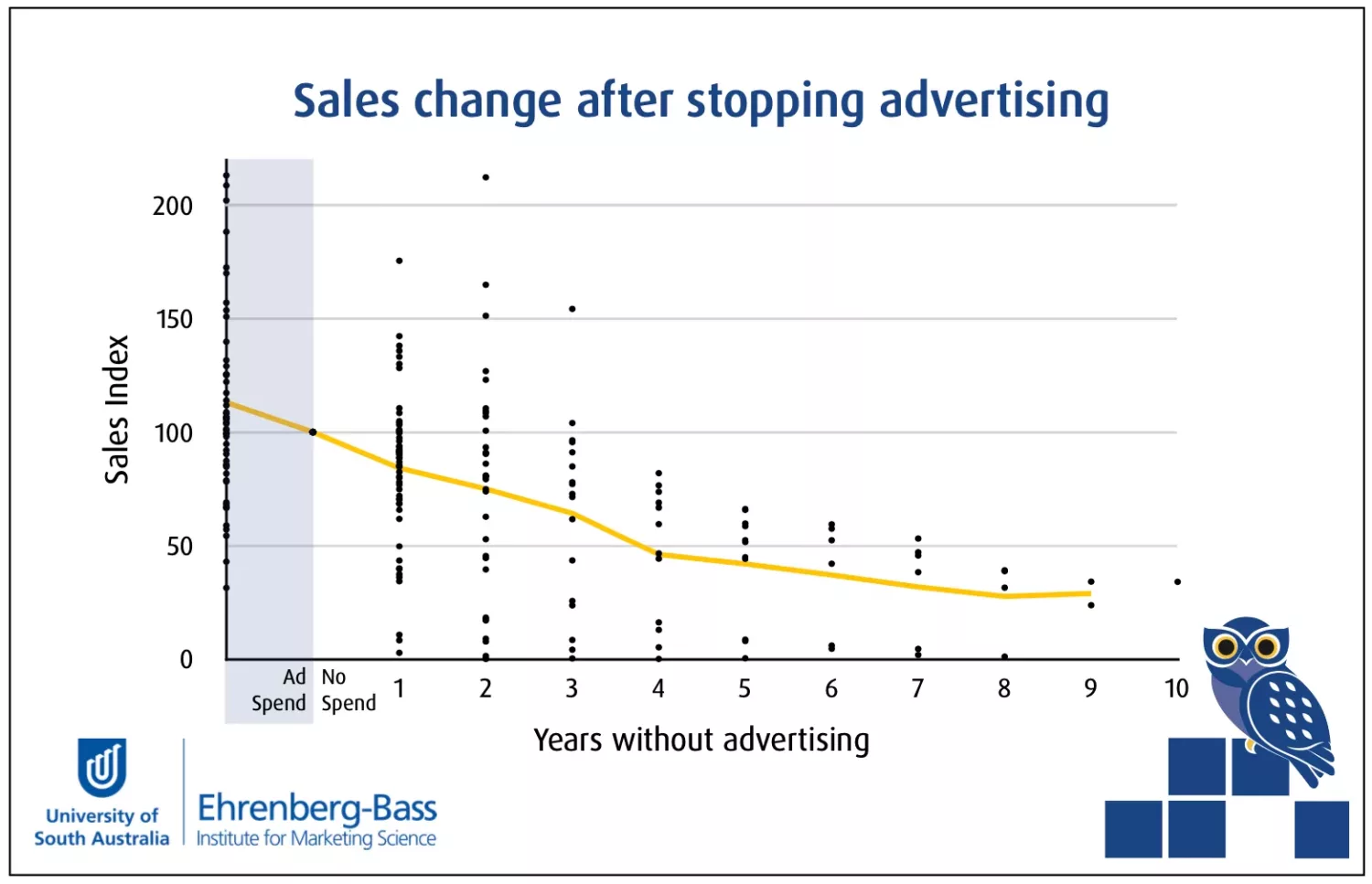

This chart looks suspiciously like another from our pals at Ehrenberg-Bass:

Source: Ehrenberg-Bass “What happens when brands stop advertising”

Without marketing, mental availability falls over time. So do sales … and a few other things like spontaneous awareness, prompted awareness, consideration (yikes) and trustworthiness (also yikes).

Source: WARC “Direct Line Group: They went short, we went long”

But something a little more interesting and perhaps slightly less obvious happened to Privilege insurance.

If Privilege was the more expensive option, 93%-99% of buyers would choose Churchill, which makes sense.

If they were the same price, 83% of buyers would choose Churchill.

But if Churchill was the slightly more expensive option — between £10 and £19 — 33% of people would still choose Churchill. Why?

Trust.

Nearly all of the mental availability Privilege had built over the years eroded away. And for consumers, choosing an unknown or barely remembered insurance brand felt like a bigger risk.

It goes back to our System 1, satisfier brains — people crave certainty and will pay more for it.

Next time, we’ll discuss why building a strong brand is more important than ever. See you then.

Sources!

“Don’t cut ad spend in a crisis” – Mark Ritson, Marketing Week

“What happens when brands stop advertising” – Ehrenberg-Bass