4 out of 5 marketers recommend …

One of our eagle-eyed readers noticed something odd in last week’s Dispatch … the phrase “meaningful differentiation.”

If you’ve read How Brands Grow, you’ll know that Professor Byron Sharp thinks differentiation doesn’t matter all that much. Mark Ritson disagrees.

Professor Mark Ritson is a brand and marketing consultant from England. He’s sardonic, sweary, smart, usually right, always interesting … and not someone you want yelling at you. He’s sort of like the Gordon Ramsay of marketing.

And he makes a very excellent point about the whole differentiation vs. distinctiveness debate. He thinks there shouldn’t be one.

First, a very quick history of differentiation.

“Your brand should stand for something unique and valuable.” - Rosser Reeves

Differentiation began in the 1940s with Rosser Reeves, who believed every brand had to have a Unique Selling Proposition, emphasis ours. And his. He very much emphasized “unique.”

According to Reeves, “unique” means owning a feature or benefit that your competitors do not and cannot offer.

Let’s say you’re the CMO of a chewing gum brand. One of your competitors promises “long-lasting flavor”, another cites the approval of 4 out of 5 dentists.

You can’t promise either because they’ve been claimed. So you lean into “fresh breath.” And all your comms, consumer touch points, product development, etc. flow from there.

(By the way, is “long-lasting flavor” really a feature you couldn’t offer? Is “fresh breath” a benefit that your competitors couldn’t deliver on?)

Fast forward 20 years or so, and we get “Differentiate or Die” by Jack Trout.

Trout was not exaggerating for comedic effect. He believed that brands need to climb a hill, ruthlessly conquer and relentlessly defend that hill … or literally die on it.

Brand managers and CMOs began contorting themselves into shapes that only Cirque du Soleil performers should attempt in order to find something singularly unique about their products.

Sometimes it’s easy. Maybe you’re a challenger gum brand offering a new, innovative thing no one’s seen before. Chewing gum with a gooey, minty center, for example. Cool.

But finding something absolutely unique about your brand (and then owning it) is nearly impossible.

Then, Byron Sharp and Jenni Romaniuk of the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute came along.

In How Brands Grow, Sharp makes the case that consumers don’t really understand or care about the difference between brands within a category.

Customers are, as Sharp put it, “polygamously loyal,” and most people have a handful of brands they reach for in a buying situation.

If Trident isn’t on the shelf, buyers might reach for Orbit. If that’s not available for some reason, they’ll choose Ice Breakers or another brand they’ve heard of.

Sharp argues that brands should focus on “meaningless distinctiveness” instead.

Distinctiveness is all about making your brand easily memorable and identifiable.

You build distinctiveness with distinctive brand assets — your logo, colors, tagline, jingle, packaging, characters, etc. These are the codes and cues people use to remember you and find you on a crowded shelf.

And that? Is incredibly important. Distinctiveness is good. Jenni Romaniuk wrote the book on distinctiveness and building distinctive brand assets.

But Sharp pits distinctiveness and differentiation against each other. Differentiation was the old way; distinctiveness is the new and better way.

Ritson argues that this is a bit silly.

Because brands within a category are different, and Sharp says as much in Chapter 8 of How Brands Grow.

Maybe they’re not uniquely different, but they are relatively different.

There’s no absolute difference between Orbit and Trident. There’s barely a functional difference between them.

But you might choose Orbit if you want to impress a date and Trident if you want to impress your dentist.

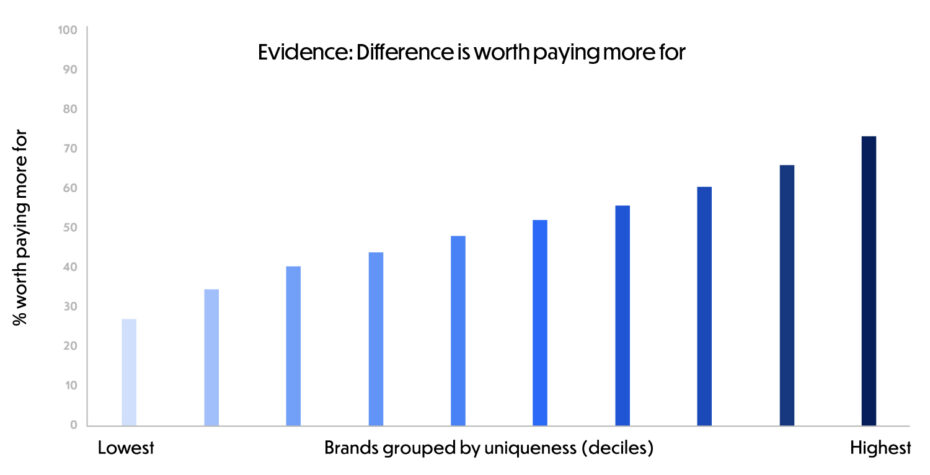

If there was no evidence that differentiation matters, fine. Then it’s just brands showing off to an audience of no one because buyers don’t care. Every brand is a commodity and not worth paying a premium for.

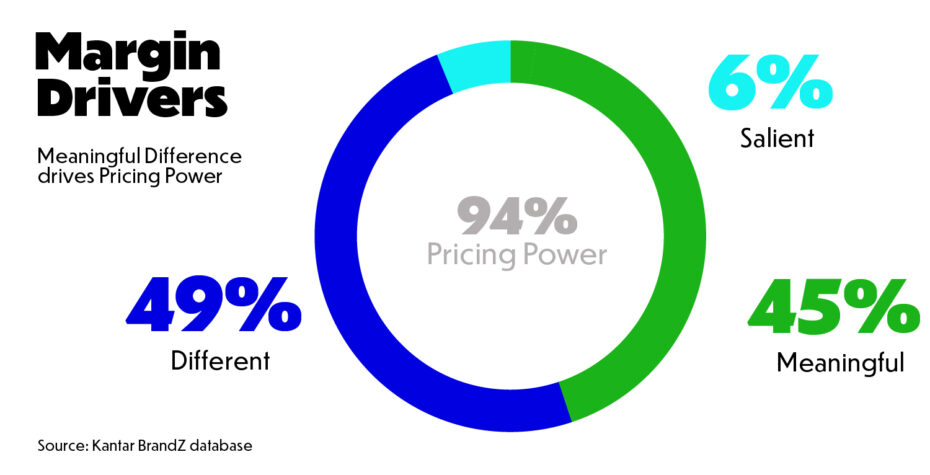

But according to data from Kantar, brands are able to charge a premium because they are different in ways that matter to consumers.

Salience (distinctiveness) is important, but meaningful differentiation drives margins and revenue.

So if people are willing to pay more for Brand A because it solves a problem in a way they think is better than Brand B, then it matters.

Yes, distinctiveness is important. So is differentiation.

Mark Ritson’s point is … why not use both?

See you next time.

Sources!